Legalise, decriminalise, or prohibit? Cannabis, the most popular drug in France, is a contentious issue. But this complex debate is often reduced to a binary argument between those for and those against. It’s made more difficult by some people confusing legalisation and decriminalisation.

WERBUNG

WERBUNG

WERBUNG

WERBUNG

Uruguay took a serious step towards legalising cannabis when “MPs approved a bill”:https://www.euronews.com/2013/08/01/cannabis-legalised-in-uruguay/ this summer, a few months after the states of Colorado and Washington did the same in the US.

But this bill has to be placed in the context of drug traffickers’ extreme violence, which South American countries have to fight against. This situation is leading to a major shift in drug policies in North and South America but also in some European countries such as the UK.

Two international organisations, the Global Commission on Drugs (non-governmental) and the Organization of American States (inter-governmental) have initiated high-level lobbying to channel international and national policies towards prevention and care, rather than prohibition, which has prevailed for the last forty years. The Global Commission on Drugs has published a report to to defend its position and which bears the name of its main slogan ‘war on drugs’..

A debate on the edge

Anne Coppel, a sociologist who has founded the AFR (‘French Association for the Drug Use Risks Reduction’), agrees with this conclusion of failure of prohibitionist and aggressive drug policies. She considers that prohibiting drugs has “polarised the debate on cannabis, with politicians’ stands reduced to ‘being lax’ or ‘being authoritarian’.” In her book ‘Drogue sortir de l’impasse’ (Drugs, Breaking the Deadlock, by Anne Coppel & Olivier Doubre, Ed. La Découverte), she sets her stall out in the introduction : “those defending the moral order on one side, libertarians on the other; the public debate is stuck between principled positions.”

Legalisation, regulation, decriminalisation: Definitions

These words do not correspond to real fixed and limited legal rules. Variations are thus possible in each case.

Legalisation – Legalisation of cannabis is often used to refer to a partial legalisation, regulated by the state : it consists of making, selling and possessing cannabis legally within a framework set by the state. For instance: making it illegal to sell it to the underage, like for tobacco or alcohol; making it illegal to sell it outside a legal shop like a tobacconist; or making it legal only for therapeutic reasons.

Legalising cannabis entirely without any restriction would mean it becomes a consumer good like any other. We can then speak of liberalisation.

Legalising cannabis could include allowing it to be grown, either by a national farming industry or by single individuals, depending on choices made by each country.

Decriminalisation – Decriminalising cannabis means sanctions for cannabis use are not applied. It is still forbidden: cannabis is still not allowed, selling it and trafficking are too, but possessing and using it are no longer punished. The crime is either removed from the law or penalities are reduced.

Political parties are in favor of decriminalising (greens, communists, most of the socialists, some politicians from the right UMP) or against it (most of the right UMP, centrists and the far-right National Front) and accuse one another of either being too soft or too hard on drugs. Beyond these stands, the taboo lingers on. This taboo is maintained, say KShoo (pronounced ‘cashew’) from the CIRC (Collective of Information and Research on Cannabis) by the French law which forbids to present narcotics positively, meaning that “the debate cannot take place”.

Decriminalising cannabis regularly comes back in the political debate but politicians tend to simplify their arguments. In June 2012, for instance, Cécile Duflot, ecologist and Minister of Housing, stated she is in favour of decriminalising cannabis. Arnaud Montbourg, a socialist from the same government and Minister of Industrial Renewal then made a slightly polarising statement on BFMTV news channel: “I don’t want my kids to be able to buy cannabis in a supermarket”.

In France, there are so many people demanding that cannabis should be fully legalised and regulated by the state. “France is not like Uruguay or Colombia” says Danièle Jourdain Menninger, president of the Joint ministerial Mission Against Drugs and Addictions (MiLDT) since September 2012.

CIRC is one of these few in favour of legalising cannabis. On its website, the organisation states “supporting strongly a complete regulation of recreative cannabis” within a frame that is “joint, cooperative and non-profit”, which organises the traceability of the products and which forbids “brand advertising”. For them, it is a matter of personnel freedom of “doing what you like with your own body”. “Are we free to poison ourselves as long as we don’t poison anyone else?” asks KShoo. It is society duty to then “help those who suffer” he adds.

Giving out information on how to consume cannabis while limiting and avoiding risks is another very important point for CIRC that is impossible to deal with under the regime of prohibition.

But the main point for those in favour of legalising cannabis, a point that motivated Uruguay, is to cut out drug traffickers’ sources: suppression of competition, mafia networks, and a lack of security. “I think that the stronger the repression, the more violence” says Anne Coppel bluntly.

The Global Commission on Drugs draws the same conclusion and gives out several recommendations in its report: breaking up the taboo is the first one… They are, among others, offering care for drug dependence and substitution treatments, investing in evidence-based prevention and experimenting with new legal regulations.

Leaving violence behind or trivializing the use of cannabis?

In France, decriminalising is the most serious alternative to prohibition. It is generally understood as the decriminalisation of use and possession. 8,760 people have been sent to prison for illegal use of narcotics in 2011 (out of a total of 38,977 convictions). “Repression has been accentuated by the minimum sentences system in 2007; they were not created for drug cases but they also apply to drug affairs” explains Anne Coppel, sociologist. Therefore, for those in favour of decriminalising cannabis, one of the main purposes of modifying the 1970 law would be to take drug users out of prison and move them back into the addiction-care system.

As for legalisation, decriminalisation is seen as a way to try and weaken illegal trafficking and the violence which often comes with it. KShoo, spokesperson for the CIRC, sums this idea up: “the 1970 law is criminogenic; it creates crime where there is none, a crime without a victim. Smokers make a choice, taking the risk to become dependent.” The CIRC even calls this law a “pyromaniac fireman” one.

Serge Lebigot is the president of the organization ‘Parents against drug’ (‘Parents contre la drogue). He used the same expression in a round-table at the French Senate during an information mission about addiction to express a radically opposite opinion. “At the bottom line, these policies surrender in front of the drugs problem. […] Some will bring already-made answers to this fact. ‘We have a problem with cannabis? Let’s legalise it!’ It is equivalent to saying: ‘the house is burning? Let’s burn all the houses!’ These ‘pyromaniac-fireman’ policies are preposterous”.

For those in favour of prohibition, the main risk of decriminalising cannabis is to trivialise it. Marie-Françoise Camus, from ‘The Lighthouse, Families dealing with drugs’ (‘Familles face à la drogue – le Phare’), “being officially or informaly so permissive do so much damage”. It pushes young people to take drugs because “among contradictory messages, young people keep the ones that they like best”.

She adds: “pro-drugs lobbies like Act up [sic] don’t care much about the fact that a part of our young people, who could have studied, be managers, do something positive with their lives, end up being a burden for society”. This opinion, she says “is not understood by politicians”.

Bernard Mars, gendarme and captain of Lyon Juvenile Delinquency Prevention Brigade (BPDJ), reports the same difficulty to pass on the message to young people. He speaks in primary and high schools of the Rhone county and says the way the debate is dealt with in France has effects on children: “We, adults, are not very clear for our teenagers. Considering what kind of speech I give is an adult’s job; teenagers send us back to our own contradictions.”

Everyone agrees, CIRC included, to say that cannabis is not a product like any other. In June 2012 again, following Cécile Duflot’s declarations, medicine and pharmacy academies published a common press release to warn against cannabis dangers [in French]. They point out, as the doctors we met from the addiction centre of a hospital also noted, the fact that cannabis today contains “a more concentrated active ingredient […] it has been multiplied by 5 or 10 in 40 years.” They also worry about the new ways to consume cannabis, such as waterpipes “which almost immediately deliver high quantities of THC to the brain”.

Both academies list the health problem induced by cannabis consumption and take a clear stand: “Decriminalising cannabis use would have harmful consequences on public health in our country, especially among young people, by implying that it is a harmless habit”. They refer to recent neuroscientific research that confirms that cannabis consumption is particularly noxious for an immature brain, that of children, teenagers and young adults.

Another obstacle to realising how toxic cannabis can be is underlined by the addictologists of L’Arbresle hospital. More diffused than some other drugs, it lingers in the body for several days, giving the impression it doesn’t create any craving.

Dr. Brinnel, chief doctor at the addiction center of L’Arbresle hospital, considers that for a physician “it is ethically impossible to support decriminalising cannabis; I cannot be in favour of such a position”. He thinks that “it would mean abandoning the population to a toxic product”. It compares the situation to tobacco for which price rises does not make the numbers of smokers drop, “even though each new rise bring us new patients”. He qualifies his position: “we deal with patients every day, so we’re not objective. But, still…”.

Acting beyond the divisions

The debate is locked but public policies have changed since the beginning of prohibition. Sociologist Anne Coppel thinks “we should have achievable objectives, deal with problems as best as we can, knowing we cannot eradicate drugs.” Act through concrete programmes is also the choice of Danièle Jourdain Menninger, presidente of the MiLDT: “it is more efficient than just ideological stands”.

The new government plan against drugs and addictive behaviors 2013-2017

This new plan was passed on September 19 by a joint ministerial committee chaired by the Prime minister. 50 million euros have been granted for its first two years, to which has to be added a part of each ministry involved. This plan is led by the Joint ministerial Mission Against Drugs and Addictions (MiLDT). It was built on six months of consultations of people working in the field.

Here are its three priorities : 2. “Built public action intoobservation, research and evaluation ”. Working from evidence-based information, Danièle Jourdain Menninger hopes to avoid ideological stands. Research will look into “understanding addictive behaviours”, pharmaceutical treatments and “therapeutic strategies”. 3. “Reducing risks and sanitary and social damages” by working closer to “the most exposed populations”: women, persons isolated from care, the world of work. 4. Fighting trafic and delinquency linked to drugs. “Making security, tranquility and public health stronger” are the main goals. A part of this point will be dedicated to the designer drugs and drugs sold on the internet. Drug consumption rooms are also included in that part of the plan.

The first axe d’action ‘de traverse’ was reducing risks for drug users. The National Health and Medical Research Institute (INSERM) sums up this philosophy: “If you can, do not take drugs. If you cannot, sniff it instead of injecting it. If you cannot sniff, use a clean syringe. If you cannot, use your own again. If you are sharing a syringe, at least clean it with bleach.”

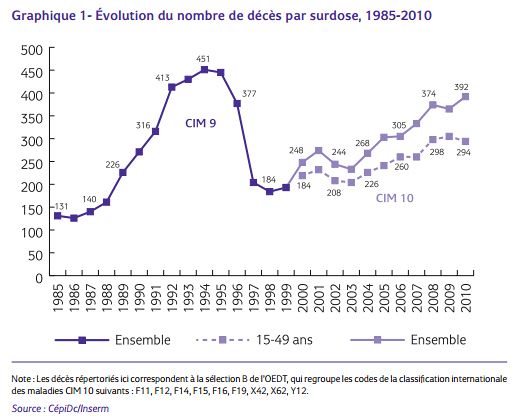

In the 1980s, AIDS started being a serious public health problem. In 1987, Michèle Barzach, then Health Minister, signed a decree authorising the free selling of syringes in pharmacies. This first measure has been repeated every year since then. It has helped reduce the HIV transmission among users consuming drugs intravenously. The number of drugs users who take part in the syringes exchange program and are infected by HIV has dropped from 19.3% to 10.8% between 1998 and 2004. This policy “has also reduced the number of overdoses by 80%” explains Anne Coppel. In 1994, Simone Veil reinforced this programme and established opioid replacement therapy.

The latest two evolutions in this risk reduction are legalising some cannabis-based medications and the opening of a drug consumption room in Paris (a project that has been delayed on October 8 by the Council of State). For Marie-Françoise Camus, president of ‘The Lighthouse, Families dealing with drugs’ (‘Le Phare – Familles face à la drogue’), this drug consumption room “is a catastrophe”; for MiLDT it is a project from the new governmental plan against drugs and addictive behaviours [in French] that was published on September 19. Making it an acceptable project for the surrounding population is another point.

Sociologist Anne Coppel has been defending that idea since the mid-1990s and calls for a multi-disciplinary approach. She insists on how important it is to bring different views on the issue, should they be medical, legal or sociological: “drug policies deeply depend on other societal choices: schools or prisons, war or peace, tax havens or control over financial exchanges… We must not leave this issue to experts only, even if their expertise is necessary” (‘Drogue sortir de l’impasse’ – Drugs, Breaking the Deadlock, by Anne Coppel & Olivier Doubre, Ed. La Découverte).

Prevention at heart

Prevention actions as told by our contacts

Danièle Jourdain Menninger, MiLDT

“In partnership with the National Institute for Health Prevention and Education (INPES), we will train PMI workers (Maternal and Child Protection) on addictive behaviours issues so they can help the young mothers they meet daily. We will therefore be able to get in touch with a population that would otherwise be completely out our radar on this issue.”

“We give our support to risk reduction missions abroad. We helped create, with Doctors of the World, a drug consumption room for women in Kabul. We all know how hard it is being a woman in Afghanistan, how hard it is being a drug addict in Afghanistan. So imagine being a drug-addicted woman in Kabul…”

Bernard Mars, BPDJ

“We work by chatting freely, debating and exchanging for an hour and a half with the teenagers, and letting them debate between themselves. We bring them information to think over. […] Teenagers often start by testing us with a question on police violence. Quickly, the teenagers ask us very personal questions. The one that regularly comes back on the addiction issue is 'how can I help a friend that is a drug addict?' Sometimes, it is difficult for us to answer. In such a case, we go back to the general problem to show them how tricky it can be and how difficult it can be to find a solution. We use their own words and some scientific knowledge. We try and be humble about this knowledge.”

Marie-Françoise Camus, Le Phare

“We meet pupils directly in the classrooms when we are called by schools. A part of our speech is made up of testimonies. Then we give information to the teenagers, about what happens in their brain when they take drugs for instance. Another part is done on paper: we ask them questions, such as 'do you take drugs?'. Most of the time they answer very sincerely. They are often moved by the testimonies. Sometimes they are given by young people like them even though it is rarely the case as we prefer that these kids go back to studying. More often they are given by adults that can be 50 years old. It is still very poignant for these teenagers as it is reality; they see someone in the flesh. [...] Parents do not tell their stories because I consider that we do not have to speak about our children's life in public; our children's life do not belong to us.”

There is a common ground, even though everyone does not think of it as important : prevention. For the sociologist Anne Coppel, “the only tool that works is prevention, information”. For Bernard Mars, captain of the BPDJ, whose work relies on prevention, “there is no good repression, without a good prevention”. For CIRC, a Collective of Information and Research on Cannabis, informing people is its ‘raison d’etre’.

Even though they are ideologically opposite, ‘The Lighthouse, Families dealing with drugs’ deals a lot with prevention in high schools. Serge Lebigot, from ‘Parents against drug’ insisted in the Senate round-table in 2011 that his organisation wants a prevention policy: “I mean a serious prevention, starting when children are very young. We must neither trivialise nor dramatise drugs”. It is a position that Bernard Mars and his colleagues also favour: “We give them information to think over. We do not trivialise; we do not dramatise”. Finally, prevention is the priority number two, after evidence-based research, of the new plan of the Joint ministerial Mission Against Drugs and Addictions (MiLDT).

Since 1989, this prevention is mainly aimed by France towards young people so as to “stop, delay or limit drug use among youg people” (priority 2, objective 1 of the governmental plan 2013-2017). The CIRC regrets such a choice says its spokesperson aged 40: “just as if they are only young people who smoke cannabis”, adding: “It is not by stigmatising young people that we will teach them how to use drugs intelligently.”

A fact that MiLDT took into consideration. “We did not plan any major communication campaign to say ‘drugs=danger‘” explains its director. It is a radically different choice from the previous management team which had made a campaign that had been higly critised by several organisations. On the contrary, says Danièle Jourdain Menninger “we are going to promote a MiLDT 2.0, using new technologies, the language and the codes that young people understand; we will communicate on social networks”. Danièle Jourdain Menninger explains that the whole programme is built on a preventive approach founded on an evidence-based research and evaluation (priority number 1 of the governement plan).

In this complex debate, Bernard Mars, who meets young people daily and is aware of the questions they have and how they try cannabis, makes a very simple statement that ideolgical stands would almost erase: “when we say that one 17 year-old out of two has touched cannabis at least once in his life, what it is also important to note is that it means that one out of two has never touched it”.

Our contacts

Danièle Jourdain Menninger, presidente of Joint ministerial Mission Against Drugs and Addictions (Mission interministérielle de lutte contre la drogue et la toxicomanie)

Founded in 1982, MiDLT coordinates several government ministries' work on drugs. It also represents France internationally on these issues.

Bernard Mars, gendarme and captain of Lyon Juvenile Delinquency Prevention Brigade (BPDJ)

Six gendarmes (three men and three women) founded this brigade in 1997. They intervene in high schools across the Rhone département on the following themes: law that protects, internet, pupils' harassment, addiction and, finally, violence within young couples. The brigade also collects under-age victims' testimonies.

KShoo, spokesperson of the Collective of Information and Research on Cannabis (CIRC)

CIRC was founded in 1991. Its aim is to "preventively collect and spread information about cannabis". It advocates a change in the law that regulates drugs and argues that cannabis should be made legal.

Marie-Françoise Camus, president of the organisation ‘The Lighthouse, Families dealing with drugs’

‘The Lighthouse, Families dealing with drugs’ was founded in 1996. It helps and backs families dealing with a child's addiction. It has a telephone helpline and organises meetings. It also intervenes in high schools across the Rhone département.

Anne Coppel, sociologist

Anne Coppel is a sociologist. She works on drugs issues, risk reduction and addiction. She co-founded and is honorary president of the 'French Association for the Drug Use Risks Reduction' (AFR).